Earlier this year, Hurricane Helene tore through my hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, as it carved a 500-mile path of destruction across the southeastern United States. The storm unleashed powerful winds and a relentless four-day downpour, toppling thousands of trees and transforming once-gentle streams into raging rivers. Entire mountain towns and large swaths of one of the world’s most biologically diverse temperate ecosystems were devastated. Helene’s terrible human toll and economic impact are already apparent – it ranks as the third-deadliest hurricane of the modern era and economic losses will likely exceed $50 billion – but what about its impact on wildlife?

While we routinely measure infrastructure damage and count human casualties and displaced persons after disasters — and have robust tools for doing so, we rarely conduct comprehensive assessments to evaluate the full spectrum of disaster-related impacts on ecosystems and their non-human inhabitants. When researchers do attempt to measure such impacts, the numbers are staggering. For instance, a study from the University of Sydney and the World Wildlife Fund revealed that the Australian megafires of 2019-2020 killed or displaced an estimated three billion animals and burned nearly 13 billion hectares of habitat. Wildlife mortality and habitat destruction from Hurricane Helene will probably never be fully quantified. Yet, we can be sure that the losses are dreadful.

Beyond the immediate fatalities and injuries, disasters have long-term, negative effects on both individuals and on entire species. When large areas of habitat are lost, wildlife struggle to find food, water, and shelter. As a result, animals may be forced to leave their homes in search of new, habitable areas. Along the way, they often face the danger of being struck by vehicles, and upon arrival, their new habitat may already be occupied by other species, pushing the area beyond its carrying capacity—or by humans who view the newcomers as pests.

Large-scale disasters can be especially devastating for vulnerable and endangered species already struggling to maintain their populations and avoid extinction. Globally, more than 46,000 known species are at risk of extinction. Many of these cling to existence with a few hundred or a few thousand individuals, or occupy very limited ranges that are highly susceptible to destruction. For example, the endangered Spruce-Fir Moss Spider is found only on 23 peaks in western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, and southwest Virginia. Much or all of this range could easily be wiped out by a single catastrophic event.

A Growing Concern

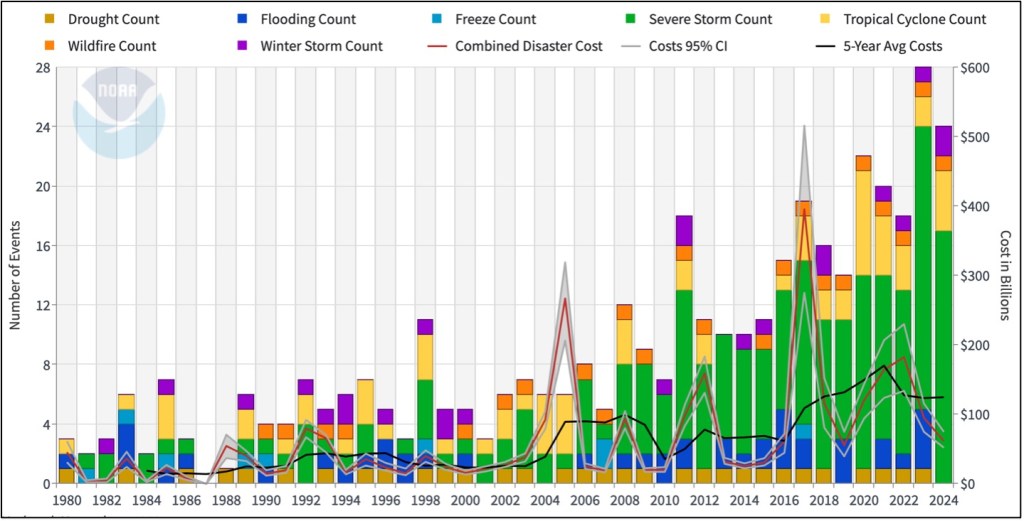

The number of major droughts, floods, hurricanes, wildfires, and other weather and climate-related disasters in the U.S. has increased dramatically over the last forty years, from an average 3.3 per year in the 1980s to 17+ from 2014 through 2024. This year is turning out to be one of the worst on record. As of November 1, 2024, the National Oceanic and Administration (NOAA) has registered 24 weather and climate disasters with losses exceeding $1 billion. Of course, though a common metric of disaster severity, economic impact is just one dimension of harm. Globally, natural disaster frequency has exhibited a similar pattern. According to the International Disaster Database (EM-DAT), major disaster events have increased from 100 per year in the 1970s to around 400 events per year in the past 20 years.

Many scientists believe we may be stuck in a positive feedback loop of rapid onset disasters (droughts, hurricanes, floods, wildfires, etc.) and slow onset disasters (acidification of the oceans, climate change, species extinction, etc.) whereby the effects of the former amplify the latter and vice versa. For instance, wildfires increase the amount of carbon in the atmosphere by burning vegetation, which in turn contributes to global warming. As the climate warms, conditions become more conducive to intense wildfires, creating a vicious cycle where one disaster exacerbates the conditions that make future disasters more likely. In both slow and rapid onset disasters, the positive feedback loop means that each event not only causes immediate damage but also sets the stage for increasingly severe future events, deepening the overall crisis and complicating efforts to adapt to and mitigate the impacts.

It will be the challenge of our time to avert the worst of the ecological crisis that is even now unfolding. As we struggle to cope with the consequences, multilateral institutions, governments (from national to local), non-governmental organizations, and individuals must all act to break this vicious cycle and begin to restore what has been lost.

Ways You Can Help

After a disaster, wildlife, like humans, needs immediate access to food, water, and shelter. Simple actions like putting up bird feeders or creating temporary shelter can offer critical support. Additionally, in the aftermath of disasters, wildlife rescue and rehabilitation efforts are crucial, but often under-resourced. Volunteering with or giving supplies to organizations dedicated to this work can make a significant difference. Beyond supporting immediate relief, you can get involved in citizen science initiatives that play an important role in assessing the impacts of disasters and in helping scientists to aid vulnerable species. Finally, you can contribute to long-term solutions, such as habitat restoration, the creation of wildlife corridors, and the development of more disaster-resilient landscapes—efforts that enhance wildlife survival both now and, especially, during times of crisis.

Emergency Food, Water and Shelter

Wildlife survivors have the same basic needs as humans. If you have a small yard or even an apartment balcony, put up bird feeders and waterers. Inexpensive options are readily available at local hardware stores and online. If you have the budget and the space to safely feed larger game, such as deer and wild turkeys, you can install or build DYI feeders and waterers. Similarly, you can create temporary sanctuaries where displaced or injured wildlife can find shelter. There are many off-the-shelf houses available for birds and small mammals and you can easily find designs online to build your own. Also, after a storm can be an ideal time to build habitat brush piles, as you will likely have plenty of yard debris. Composed of stacked woody debris and loose leaf litter, these piles offer excellent shelter for small mammals like chipmunks and squirrels, as well as amphibians and reptiles such as salamanders and snakes. Weasels, foxes, and hawks also utilize them for both shelter and hunting. Start by using larger limbs and logs to create a sturdy base, then add layers of smaller branches, leaves, and other vegetation on top. Over time, the smaller materials will break down, enriching the soil and supporting invertebrates, while the larger branches will continue to provide vertical cover for wildlife.

Rescue and Rehabilitation

Nonprofit wildlife rescue and rehabilitation organizations are chronically understaffed and underfunded. This means they often need dedicated volunteers to locate, transport and treat injured or orphaned animals and to provide other support for their overall operations. In my area, Appalachian Wildlife Refuge has provided care for more than 8,000 wild animals over the past 10 years and continues doing this life-saving work after Hurricane Helene. They are regularly looking for volunteers to support daily operations, transport wildlife, and answer calls to their Wildlife Hotline. For your safety, make sure you find an established organization experienced in working with wildlife. Also, keep in mind that there are regulations about which wildlife species people can handle. Often only certified rehabilitators can handle wild animals, and typically, only state wildlife agencies are permitted to work with large mammals like black bears and with rabies vector species, including foxes, raccoons, and skunks.

Monitor and Assess Impact

Citizen science plays a crucial role in wildlife monitoring and assessment efforts, harnessing the power of everyday people to collect valuable data that would be too costly to obtain otherwise. Smartphone apps, trail cameras, GPS tracking systems, and other technologies allow individuals to contribute data in real time, often with minimal training. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology is one of the most far reaching and successful wildlife-focused citizen science initiatives. Hundreds of thousands of people around the world contribute bird observations each year, which scientists use to study how birds are affected by habitat loss, pollution, disease, climate, and other environmental changes. Not only does citizen science help further wildlife conservation, but it also fosters a deeper connection between communities and the natural world by empowering people to be active participants in protecting local ecosystems.

Habitat Restoration

Degraded landscapes are all around us, often as close as our own backyard. Replacing some of a grass lawn with native vegetation is a great way to support wildlife. Creating healthier habitat provides food, shelter, and breeding grounds for a wide range of species. This is especially important after a disaster because so much habitat has been lost or damaged. Once you are done making your own property friendly to wildlife, look for opportunities to help restore parks, nature preserves and other land that can serve as habitat. Conservation organizations often recruit volunteers for field work, such as invasive species removal, native tree and vegetation planting, trail maintenance, clean-ups, and native seed collection. For example, The Nature Conservancy’s Nature Allies program offers volunteer opportunities in more than 20 U.S. states. Beyond the physical work, volunteering to protect habitat helps raise awareness about the importance of conservation and fosters a sense of stewardship in local communities.

Wildlife Corridors

It is difficult to physically assist wildlife during a disaster because capturing and transporting many species requires specialized skills and equipment, because wildlife is disbursed over vast areas, and because wild animals typically avoid contact with humans. Nevertheless, there are meaningful actions we can take. We can start by creating more wildlife corridors between habitat fragments, as well as safer road and railroad crossings, to help animals move across the landscape. These routes enable wildlife to travel across their historic habitat ranges under normal conditions, and they can also function as evacuation paths during times of disaster. The Wildlands Network is an excellent resource if you want to get involved in creating wildlife corridors and safer road crossings in your community.

Wildlife Disaster Planning and Response

If you are a conservation or wildlife professional, consider advocating for the inclusion of wildlife in disaster management planning where you live; support the development of disaster-related wildlife rescue guidelines; and/or join a wildlife emergency-rescue team. Fortunately, with increasing consideration of pets and livestock in disaster planning and response in recent years, precedent has been set for these actions.

The loss of at least 150,000 pets during Hurricane Katrina and people’s resistance to evacuate without their pets led Congress to pass the Pets Evacuation and Transportation Standards Act (PETS) in 2006. PETS requires states, cities and counties to address the needs of individuals with household pets and service animals if they request federal funding for disaster planning. More than 30 states have now amended their disaster relief plans to include provisions for pets before, during, and following a major disaster or emergency. Furthermore, PETS allows the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to provide funding to states and localities for the creation, operation, and maintenance of pet-friendly emergency shelters, and it permits FEMA to reimburse state and local governments for rescuing, caring for, and sheltering animals in an emergency.

Over the past two decades, society also began to rethink its responsibility to livestock during disasters. Many U.S. states have formed State Animal & Agriculture Response Teams (SART). These are typically interagency state organizations dedicated to preparing, planning, responding and recovering during animal and agricultural emergencies and disasters. Additionally, recognizing that animals are crucial to people’s livelihoods and must be protected in disasters, in 2015 United Nations’ member states voted to include livestock in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030), a comprehensive and strategic approach to reducing disaster risks and building resilience at local, national, and global level. Finally, in the mid-2000s, individuals and agencies involved in international livestock emergency response developed the Livestock Emergency Guidelines and Standards (LEGS). These standards are based on evidence-based good practices from around the world and cover assessment, design, implementation, and evaluation of livestock interventions during emergencies. The LEGS organization delivers training and awareness raising sessions both online and in-person to practitioners on four continents.

More Than Humans

Environmental degradation is undeniably a major driver of disaster risk, and healthy ecosystems play a crucial role in mitigating these risks by providing essential services like flood control and drought prevention. In our modern, urbanized, and technology-driven world, recognition of the importance of ecosystem services has served as a vital reminder of how deeply we depend on nature. However, the ecosystem services framework simply extends the utilitarian view of the human-nature relationship that has created the ecological crisis we are living. To protect what remains of the natural world, repair the damage we have caused, and build a future where both humans and nature thrive, we must shift our perspective. The eco-centric ethic espoused by deep and spiritual ecology is a compelling alternative.

Eco-centrism sharply contrasts with the anthropocentrism that dominates current thinking, including our approach to disasters and global ecological crises like climate change and the ongoing sixth mass extinction. Rather than seeing humanity as separate from nature, eco-centrism recognizes us as an integral part of the natural world, deeply connected to the health and balance of the planet. This perspective shifts the focus from human-centered interests to the well-being of the Earth as a whole, emphasizing biodiversity conservation, ecosystem restoration, and the sustainable use of natural resources. Addressing the needs of wildlife and their habitats in disaster preparedness and response is one concrete way to we can begin to heal our relationship with nature and restore the planet we share. We are all in this together!

Comments